Forget anything after, the 1986 Turbo cars really were rockets, and to handle them I really think you had to be a man. — Gerhard Berger

After almost a quarter of century of only naturally aspirated engines, this season saw the return of turbochargers to Formula One. With an estimated output of 600 horsepower, coupled with energy recovery systems for an additional 160 horsepower, a 15,000rpm rev limit plus fuel flow restrictions, these more environmentally-friendly 1.6-liter V6 turbo engines are a far cry from their predecessors.

Former F1-driver Gerhard Berger wasn’t initially impressed with the technical revolution and performance figures. In an interview with German magazine Auto Motor und Sport at the beginning of this year, the Austrian said “that 650 or 750 horsepower for an F1 car is not enough” and suggested “we could have engines with 1000 horsepower again.” Although Berger later changed his mind and hailed the new V6 engines as “pure F1”, his initial criticism wasn’t unfounded. After all, it was Gerhard Berger who had raced with the most powerful F1 car ever made.

Turbocharged engines were pioneered by Renault at the end of the 1970s, and eventually the French proved this was the way to go in F1. Alfa Romeo, BMW, Ford-Cosworth, Ferrari, Honda and Porsche (under the TAG-banner) all made turbocharged engines and over the years, their power grew and grew — up to the point of insanity.

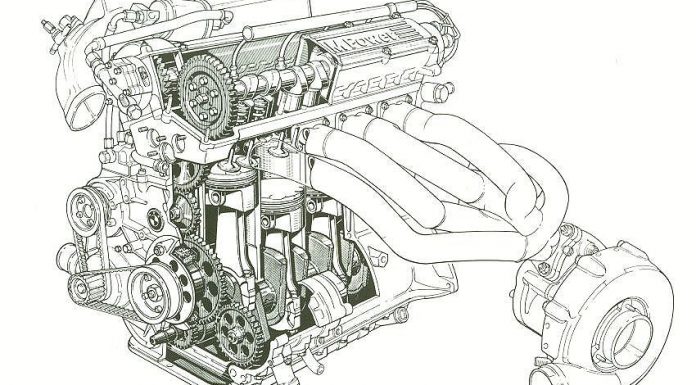

The most powerful engine of all was the BMW M12/13, a turbocharged 1.5-liter inline four-cylinder engine fitted with KKK turbocharger and a Bosch digital electronic management system. A few remarkable stories surround this engine which was based on a production block: the well-proven M10 that was introduced in 1961 and used in various racing series and cars like the BMW 2002 and the 3 Series.

Instead of casting new blocks for their turbocharged F1 project, BMW only used old ones to that had done more than 100.000 kilometers. The idea was that all the stresses of the casting process would have been worn out. If an engine block would break, it would have done so already. Or as Paul Rosche, who was in charge of BMW’s racing engine department, said about these blocks: “They are like well-hung meat.”

Even more remarkable was the process to strengthen the block’s composition — a process that hasn’t been verified. Not only were the blocks kept out in the cold and rain, but it’s also rumored that they were peed on by the engineers. As strange as it may seem, urine has a nitriding effect as it contains compounds which form hard crystals on the surface of metal. Sword makers in the middle ages discovered that steel blades quenched in urine were harder than those that weren’t (which makes you wonder what they were doing when they discovered this). So, by taking a leak the engineers contributed in effect to case hardening of the blocks.

BMW’s turbocharged M12/13 engine made its F1 debut with the Brabham team in 1982. The four-cylinder engine provided 850 horsepower in qualifying trim, but was detuned to around 640 horses for the races in order to save fuel. BMW’s debut as engine supplier wasn’t an initial success. There were some issues with the reliability and Brabham-driver Nelson Piquet even failed to qualify for the American Grand Prix in Detroit. But the next race in Montreal, with its long straights and high speeds, the BMW engine proved itself and Piquet was victorious. Eventually more success came and in 1983 Piquet became the first World Champion with a turbocharged car.

The following two years two other teams (ATS and Arrows) were powered by BMW as well, but none of the three teams were successful in beating the strong Porsche-powered McLarens. In fact, the partnership with ATS was abandoned within a year as the team proved to be quite a failure. For the 1986 season BMW started to supply engines for the new Benetton team, in addition to Brabham and Arrows. The Benetton B186 driven by Teo Fabi and Gerhard Berger would prove to be the most successful BMW-powered team as Arrows remained uncompetitive and Brabham’s radical BT55 failed to live up the expectations.

The amount of power provided by the BMW engine almost doubled since its debut. In 1986, the thirsty BMW M12/13 engine was in during the race limited to 850 horsepower, but in qualifying trim the turbo boost was maximized as far as possible. Everything was tried to get more power from the engine. For instance, the wastegate was sealed shut and within three laps the engine was gone. The exact amount of power delivered by the Bavarian four-cylinder was unknown, but according to Rosche: “It must have been around 1,400 horsepower; we don’t know for sure because the dyno didn’t go beyond 1,280 horsepower.”

Insanity is perhaps the best word to describe the F1 cars of 1986, when the race for more power peaked. Naturally aspirated engines were banned while the turbocharged engines were unrestricted. There were no rules regarding the amount of power or number of engines used. The only rule that put some limitations on performance was that the amount of usable fuel was limited at 195 liters. But since this only applied for the race, and not for qualifying, the result was as predictable as insane.

For qualifying, the BMW engine ran with 5.5 bars of boost. The power unit was paired with an equally short-lived gearbox that could withstand the engine’s tremendous power and tires that would also last only a few of laps, just enough to qualify. In those days, a F1 driver had only one lap to set a time, before his engine was turned into a molten lump of metal, or the gearbox disintegrated, or the tires burst — durability was clearly not an issue. In an interview with Atlas F1 Gerhard Berger told about the insanity of qualifying:

Then on top of it you had the qualifying. You have to remember back then, you had a qualifying lap, with qualifying turbo, with qualifying tires. You would come to the morning to practice, but all you could practice with was a certain amount of boost, you would have about 900 or 1,000 horsepower, but in the afternoon you would have around 1,400 horsepower.

So in the afternoon you had a different gearbox, because over lunchtime they would change the gears, and then you would put on one of those one lap special tires and you would go out with all that extra power and then the whole lap was a complete compromise, because all your braking points were at different points because of the extra power and speed. And of course often they would change the brakes as well, so you just had to react all the time to the changing situation. At the end, whoever did the best compromise was ahead. But it was a very special era and very very exciting for the driver and for sure you needed big balls.

The turbo engines of those days came with very poor power delivery characteristics. Especially the BMW suffered from poor throttle response and subsequent turbo lag. In an interview with the Autosport magazine, Berger said:

The car was like a bomb at circuits like Spa, Austria and Monza. And the power was unbelievable — even if the turbo delay was terrible. You’d open the throttle at the entry to the corner only to get the power at the exit. And if you missed it by five or 10 metres, there was nothing you could do — you just spun it. The lag was about one or two seconds. At Zeltweg, down the long straight to the Bosch Kurve, the car was throwing out 1400 horsepower and just kept on pushing — you felt like you were sitting on a rocket.

And what a rocket the Benetton-BMW was! Teo Fabi drove his Benetton at Zeltweg in Austria to pole position with an average speed of 256.03 km/h. At Monza in Italy Gerhard Berger was clocked with a top speed of 352.22 km/h, while Fabi passed the straight with 349.85 km/h. The five fastest cars through the speed trap were all powered by BMW. At the Mexican GP, Berger reported wheelspin in 6th gear at 345 km/h. The race in Mexico was the first win for Berger and the first win for the Benetton team, but it also was the last win for a turbocharged BMW engine. At the company’s headquarters in Munich the men in suits had decided to pull the plug on the F1 project.

The era of unlimited turbo power came to an end. Normally aspirated engines returned to F1 in 1987, while turbo engines were restricted by tighter fuel limits and boost restrictions, before they were banned altogether at the end of 1988. One of the reasons why the turbos were banned from F1 was that the cars were getting too fast.

It’s now more than twenty-five years ago that the turbocharged Benetton-BMW B186 with its tremendous power roamed the circuits and although the turbochargers are back in F1, the insane amount of power of those times surely won’t come back. The Benetton B186 is likely to remain the most powerful Formula One car ever made.

I believe the F1 cars prior to WW2 were more powerful. The big German Auto Unions and DB had some 800 plus HP

Makes one wonder how these cars tires could handle all that power as they were tall-profile bias-ply and would have twisted and buckled with an ‘all-out’ ‘hot lap’, especially when the car accelerated full throttle.

My Honda civic has way more power………

next time

next time

There was no F1 prior to WW2